Description

As the world’s attention turns to the rapidly changing Arctic, new interests are projected into an already complex landscape. In this Working Group, we discussed how the interactions of these multiple interests challenge conventional concepts and approaches to security.

1. CHALLENGES

‘It is no exaggeration to say that the Arctic has crossed a threshold leading to what systems analysts refer to as a state change’ – Oran R. Young [1]

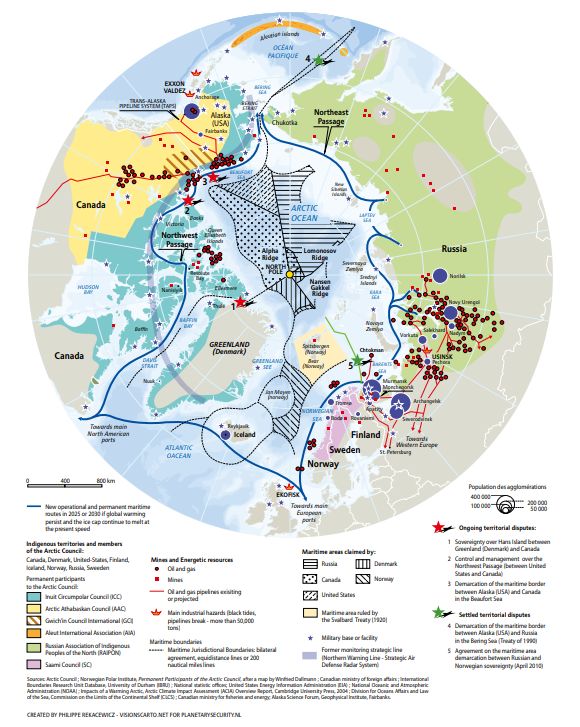

Geographically, the Arctic comprises the Arctic Ocean, which is international water, and the land surrounding it. Politically, there are eight Arctic states in this polar region: Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Canada, Russia, and the United States of America. They operate in various networks and alliances, from the regional scale of cooperation among the Nordic states to the transatlantic scope of NATO, and the increasingly global perspectives of the Arctic Council. And culturally, the Arctic is home to many Indigenous People groups, whose knowledge of the hostile Arctic environment has given them age-old resilience to change. Together, these actors and some new players will play a defining role in how the Arctic is managed in the future.

Communities in the Arctic are facing the challenge of unprecedented environmental change. According to the Arctic Council, “[t]he evidence of global warming is in no place more obvious than in the Arctic region. The Arctic has warmed rapidly during the last four decades. The magnitude of temperature increase in the Arctic is twice as large as the global increase.” The US National Snow and Ice Data Centre this year recorded the fourth-lowest extent of sea ice in satellite record, evidence that “reinforces the long-term downward trend in Arctic ice extent”.[2] As the Arctic warms, landscapes and ecosystems are being transformed, bringing new risks to human safety and security.

Arctic environmental change also presents a global challenge. The Arctic's sea ice is a major driver of global weather systems. As the ice melts, exposing dark seawater, less solar radiation is reflected back to space. Arctic change amplifies global warming. Ice and melted water from the Arctic Ocean have profound effects on ocean circulation patterns in the North Atlantic, from there influencing ocean and other climate systems over the entire planet.[3] These processes are well represented in computer models. Climate model outputs vary, but all show a clear trend towards warming in the Arctic and diminishing sea-ice extent. Unless strong efforts are put in place to mitigate climate change, the scientific consensus is that Arctic sea ice will completely disappear during the summer months before the year 2100.[4]

This increased thawing and resulting environmental change in the region is both expanding opportunities and creating new challenges in the region, which contribute to its rising significance as a global security arena. The melting ice is expected to open new commercial shipping routes, and increase natural resource exploration, provide increased access to fishing stocks, and facilitate higher tourism numbers.[5]

However, the risks and benefits of these opportunities differ for the various actors in the Arctic, and around the world. In particular, exploiting opportunities in the Arctic region can lead to escalating costs for adaptation to climate disruption elsewhere. Challenging clashes of interest are playing out at multiple levels, among Indigenous Peoples and local communities, environmental organisations, NGOs, regional groups, international bodies, commercial actors, and states. As interest in the region increases, it remains to be seen how the goals of each will interact.

Meeting the challenges of balancing these multiple interests will require local, regional, and international cooperation and foresight. As of yet, diplomatic and multilateral cooperation has existed alongside unilateral state action on the Arctic. While multi-member groups have taken shape, sovereign interests have become a politicised topic in virtually all of the surrounding states. Most recently, Russia has submitted a contested bid to the United Nations for the rights to 1.2 million square kilometres of the region.[6] Since 1982, territorial interests have been guided by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which establishes the right for countries to exploit the continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles from their shoreline.[7] Yet there are fears that this treaty could be transgressed, which presents a variety of potential territory-based scenarios. Firstly, international or regional conflict can occur if states in the region choose to pursue sovereign interests through military means. In addition, rising sea levels have the potential to alter geographical and maritime borders across the world, which could also ignite international maritime law disputes between states. Thirdly, some fear the return to land rights system based solely on a state’s ability to defend the land/water in question.[8]

2. RESPONSES

Forty-seven nations are currently engaged in one or more of the 14 international organisations dealing with Arctic affairs. Many international legal frameworks are concerned with the Arctic, especially regarding environmental and ecosystem issues.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the International Maritime Organisation play a pivotal role in pre-empting and addressing potential conflict in the Arctic region.[9] Further, the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) oversee claims by states to secure the outer limits of its continental shelf.

The Arctic Council, formally established in 1996, is a high level intergovernmental forum that provides a means for promoting co-operation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic States, with the permanent participation of representatives of the Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic, who are consulted in all negotiations and decisions. It has steadily expanded the number of observers; China, Singapore, India, Japan, and the Republic of Korea are now among the 12 non-Arctic observer countries. Meeting bi-annually, the Arctic Council issues non-binding declarations. In addition, its Working Groups produce authoritative scientific assessments on environmental change and sustainable development in the region. It currently operates three task forces charged with scoping emerging issues and proposing improved ways to deal with particularly challenging issues: the Task Force on Arctic Marine Cooperation, the Task Force on Telecommunications Infrastructure in the Arctic, and the Scientific Cooperation Task Force.

Also known as the Finnish Initiative, the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy is a non-binding yet broad-ranging agreement founded at a ministerial conference in Rovaniemi, Finland, in June 1991. All eight Arctic states are signatories to the agreement, which is widely seen as a precursor to the Arctic Council. It sets out the principles that underpin responses to Arctic challenges today: an emphasis on environmental monitoring and protection, and respect for the needs and traditions of Arctic Indigenous Peoples.

The European Union maintains an observer status in the Arctic Council, and regularly participates in meetings. On 20 January 2011, the European Parliament adopted an own-initiative report and resolution on “A sustainable EU policy for the High North”. The report indicates the need for a united, coordinated EU policy on the Arctic region, stating the EU’s priorities, identifying the potential challenges, and defining a strategy. The scope of the EU’s Arctic policy includes environment and climate change, support to Indigenous Peoples and local populations, research, monitoring and assessments, exploitation of hydrocarbons, fisheries, transport, tourism, and multilateral governance.

The Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC) is made up of the five Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Finland), Russia, and the European Commission. Established in 1993, the group attempts to facilitate sustainable cooperative development in an effort to prevent political tension between members.

Click here to download the PDF version of the map.

[1] Cited in Kraska J, Arctic Security in an Age of Climate Change (2011) (hereinafter Kraska 2011)

[2] National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC), ‘Arctic sea ice news and analysis’ (2015) http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/2015/10/2015-melt-season-in-review

[3] NSIDC, ‘All About Sea Ice’ https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/seaice/environment/global_climate.html

[4] Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Working Group I, Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Chapter 12, Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_Chapter12_FINAL.pdf; See also Figure SPM.7b in IPCC AR5 WG1 on nearly ice-free Septembers predicted by 2050. http://www.climatechange2013.org/report/reports-graphic/report-graphics/

[5] Kraska 2011

[6] Reuters, ‘Russia resubmits claim for energy-rich Arctic shelf’ (4 August 2015) http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/08/04/russia-arctic-idUSL5N10F3H920150804

[7] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Part VI, Continental Shelf, article 82 www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm

[8] Paskal C, How climate change is pushing the boundaries of security and foreign policy (June 2007 Chatham House Briefing Paper) http://www.partnershipforchange.ie/library/Report%2017%20How%20Climate%20Change%20is%20Pushing%20the%20Boundaries%20of%20Security.pdf

[9] For Russia’s Arctic claim, see Van Efferink L, ‘Arctic Geopolitics – Russia’s territorial claims, UNCLOS, the Lomonosov Ridge’ http://www.exploringgeopolitics.org/publication_efferink_van_leonhardt_arctic_geopolitics_russian_territorial_claims_unclos_lomonosov_ridge_exclusive_economic_zones_baselines_flag_planting_north_pole_navy/

3. FURTHER READING

• An image of claimed land in the Arctic region by country: http://cdn.static-economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/original-size/images/print-edition/20141220_IRM937.png

•GeoPolitics North – A geopolitics organisation with links to Arctic strategy from a variety of states: http://www.geopoliticsnorth.org/

• How climate change is pushing the boundaries of security and foreign policy: http://www.partnershipforchange.ie/library/Report%2017%20How%20Climate%20Change%20is%20Pushing%20the%20Boundaries%20of%20Security.pdf

Arctic Strategy by Country

• Kingdom of Denmark (2011 – 2020): http://usa.um.dk/en/~/media/USA/Arctic_strategy.pdf

• Sweden (2014): http://www.openaid.se/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Swedens-Strategy-for-the-Arctic-Region.pdf

• Finland (2013): http://vnk.fi/documents/10616/334509/Arktinen+strategia+2013+en.pdf/6b6fb723-40ec-4c17-b286-5b5910fbecf4

• Norway: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/report_summary/id2076191/

• Iceland: http://www.arcticportal.org/features/742-icelandic-arctic-policy-under-development

• Canada: http://www.northernstrategy.gc.ca/index-eng.asp

• United States: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/nat_arctic_strategy.pdf

This article is based on Philippe Rekacewicz (Rapporteur). "Working Group 8: Arctic Security and Conflicting Interest". In Shirleen Chin and Ronald A. Kingham (Editors). "Conference Report: Planetary Security - Peace and Cooperation in Times of Climate Change and Global Environmental Challenges, 2-3 November 2015. The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, January 2016.